Building a Financial System That Works — For Everyone

Deliver financial tools that enhance stability, deepen engagement, and drive stronger results across your entire portfolio.

Our Services

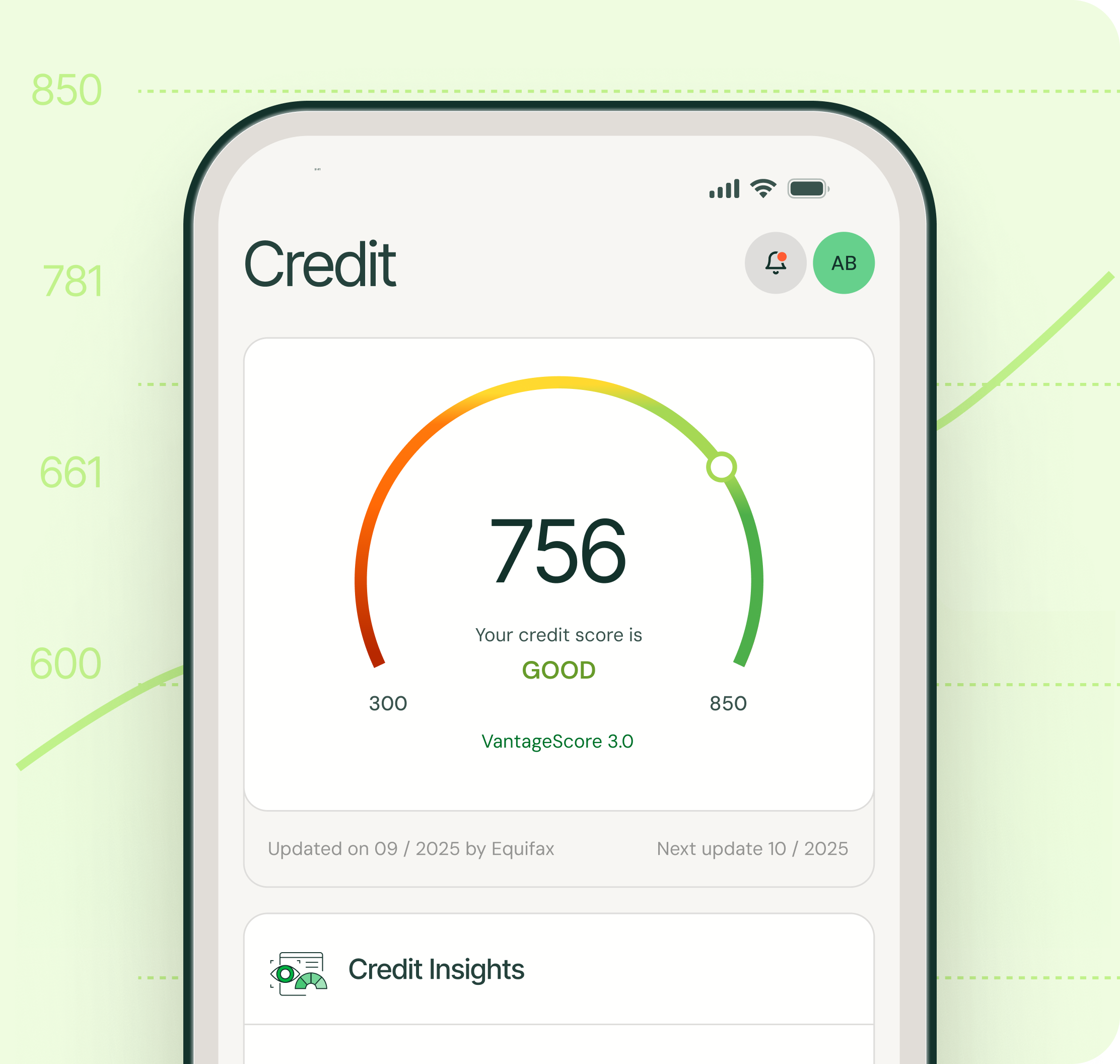

Credit Building

Turn everyday financial activity into a powerful tool for building credit, helping you strengthen relationships and create meaningful impact.

Financial Health

Empower people with insights and resources to make smarter financial decisions, fostering loyalty and long-term engagement.

Rent Payments

Offer flexible, reliable, and seamless payment experiences that give people control while boosting satisfaction and retention.

Identity & Fraud

Verify identities and prevent fraud with Esusu Identity Services, protecting trust and enhancing every interaction.

Analytics

Track payments, credit, and portfolio health in real time. Connect with partners like LeaseLock, benchmark with Lafayette x Potomac, and showcase resident impact to reduce risk and drive smarter decisions.

See What Our Clients Are Saying

Matias Recchia

Co-Founder & CEO of Keyway

Patrick Richard

Founder & CEO, Stoneweg US

Jeffrey Brodsky

Vice Chairman, Related Companies

Joanna Zabriskie

CEO & President at BH.

Dallas Tanner

CEO of Invitation Homes

We’re proud to be the rent reporting provider for some of the biggest names in real estate:

Esusu By The Numbers

Powering financial mobility at scale, unlocking billions and supporting millions.

$0M

Capital raised

$0B

Economic value

0M

Renters impacted

0M

Rental units

Outcomes You Can Count On

Rent Reporting

“I have been using Esusu for under a year. My experience with building credit and financial stability before Esusu was non existent because I didn’t have financial discipline. Esusu has had such a positive financial impact on my life with its extensive support system to help you on your financial journey. Building credit and financial stability is important to a healthy credit portfolio.”

Daphne H.

+53pts

Average credit score increase*

Rent Relief

“I began my journey with Esusu in April 2023 for rent relief program at my current housing complex, which was truly a God-send. Since then, my credit stability has improved tremendously with each on-time monthly payment and has increased my credit score and afforded me other opportunities to continue growing.”

Eugene H.

"Esusu Made Me Feel Like Part Of A Family"

Latest Articles

View BlogReady To Get Started?

Are You a Renter?

Are You a Business?

.svg)

.png)

.svg)